Page 12 - IJPS-4-2

P. 12

Child trafficking in China

example, after adopters’ pay for victims, they usually need to purchase a falsified birth certificate to legitimize their

“children” (Shen, 2013; Wang, 2015).

3.2 Geographic pattern of child trafficking

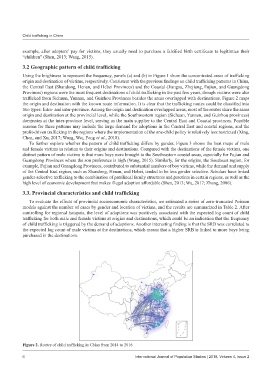

Using the brightness to represent the frequency, panels (a) and (b) in Figure 1 show the concentrated areas of trafficking

origin and destination of victims, respectively. Consistent with the previous findings on child trafficking patterns in China,

the Central East (Shandong, Henan, and Hebei Provinces) and the Coastal (Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong

Provinces) regions were the most frequent destinations of child trafficking in the past few years, though victims were also

trafficked from Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou Provinces besides the areas overlapped with destinations. Figure 2 maps

the origin and destination with the known route information. It is clear that the trafficking routes could be classified into

two types: Intra- and inter-province. Among the origin and destination overlapped areas, most of the routes share the same

origin and destination at the provincial level, while the Southwestern region (Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou provinces)

dominates at the inter-province level, serving as the main supplier to the Central East and Coastal provinces. Possible

reasons for these patterns may include the large demand for adoptions in the Central East and coastal regions, and the

profit-driven trafficking in the regions where the implementation of the one-child policy is relatively less restricted (Xing,

Chen, and Xu, 2017; Wang, Wei, Peng et al., 2018).

To further explore whether the pattern of child trafficking differs by gender, Figure 3 shows the heat maps of male

and female victims in relation to their origins and destinations. Compared with the destinations of the female victims, one

distinct pattern of male victims is that more boys were brought to the Southeastern coastal areas, especially for Fujian and

Guangdong Provinces where the son preference is high (Wang, 2015). Similarly, for the origins, the Southeast region, for

example, Fujian and Guangdong Provinces, contributed to substantial numbers of boy victims, while the demand and supply

of the Central East region, such as Shandong, Henan, and Hebei, tended to be less gender selective. Scholars have linked

gender-selective trafficking to the combination of patrilineal family structures and practices in certain regions, as well as the

high level of economic development that makes illegal adoption affordable (Shen, 2013; Wu, 2017; Zhang, 2006).

3.3. Provincial characteristics and child trafficking

To evaluate the effects of provincial socioeconomic characteristics, we estimated a series of zero-truncated Poisson

models against the number of cases by gender and location of victims, and the results are summarized in Table 2. After

controlling for regional hotspots, the level of adoptions was positively associated with the expected log count of child

trafficking for both male and female victims at origins and destinations, which could be an indication that the frequency

of child trafficking is triggered by the demand of adoptions. Another interesting finding is that the SRB was correlated to

the expected log count of male victims at the destinations, which means that a higher SRB is linked to more boys being

purchased in the destinations.

Figure 2. Routes of child trafficking in China from 2014 to 2016

6 International Journal of Population Studies | 2018, Volume 4, Issue 2