Page 38 - IJPS-6-2

P. 38

Internet use in older African Americans

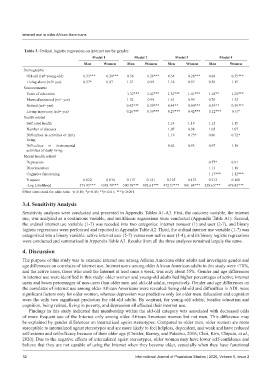

Table 3. Ordinal logistic regression on internet use by gender.

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Men Women Men Women Men Women Men Women

Demographic

Old-old (ref=young-old) 0.33*** 0.20*** 0.58 0.28*** 0.54 0.28*** 0.69 0.35***

Living alone (ref= yes) 0.57* 0.87 1.21 0.99 1.18 0.97 0.38 1.15

Socioeconomic

Years of education 1.32*** 1.42*** 1.32*** 1.41*** 1.18** 1.28***

Married/partnered (ref= yes) 1.52 0.99 1.61 0.99 0.76 1.32

Retired (ref= yes) 0.42*** 0.39*** 0.44** 0.50*** 0.39** 0.39***

Living in poverty (ref= yes) 0.26*** 0.39*** 0.27*** 0.42*** 0.12*** 0.57 +

Health-related

Self-rated health 1.14 1.19 1.12 1.15

Number of diseases 1.07 0.98 1.05 1.07

Difficulties in activities of daily 1.19 0.75* 0.86 0.72*

living

Difficulties in instrumental 0.62 0.93 0.97 1.18

activities of daily living

Mental health-related

Depression 0.77* 0.91

Discrimination 1.13 1.18

Cognitive functioning 1.17*** 1.12***

R square 0.022 0.034 0.115 0.141 0.125 0.151 0.212 0.168

-Log Likelihood 575.95*** 1038.79*** 500.78*** 892.61*** 472.57*** 841.84*** 238.65*** 476.83***

Effect sizes stand for odds ratio. p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

+

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analyses were conducted and presented in Appendix Tables A1-A3. First, the outcome variable, the internet

use, was analyzed as a continuous variable, and multilinear regressions were conducted (Appendix Table A1). Second,

the ordinal internet use variable (1-7) was recoded into two categories: internet nonuser (1) and user (2-7), and binary

logistic regressions were performed and reported in Appendix Table A2. Third, the ordinal internet use variable (1-7) was

categorized into a binary variable: active internet user (5-7) versus non-active user (1-4), and its binary logistic regressions

were conducted and summarized in Appendix Table A3. Results from all the three analyses remained largely the same.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine internet use among African American older adults and investigate gender and

age differences on correlates of internet use. Internet users among older African American adults in this study were <70%,

and the active users, those who used the Internet at least once a week, was only about 55%. Gender and age differences

in internet use were identified in this study: older women and young-old adults had higher percentages of active internet

users and lower percentages of non-users than older men and old-old adults, respectively. Gender and age differences on

the correlates of internet use among older African Americans were revealed: being old-old and difficulties in ADL were

significant factors only for older women, whereas depression was predictive only for older men. Education and cognition

were the only two significant predictors for old-old adults. By contrast, for young-old adults, besides education and

cognition, being retired, living in poverty, and depression all affected their internet use.

Findings in this study indicated that membership within the old-old category was associated with decreased odds

of more frequent use of the Internet only among older African American women but not men. This difference may

be explained by gender differences on internalized ageist stereotypes. Compared to older men, older women are more

susceptible to internalized ageist stereotypes and are more likely to feel helpless, dependent, and weak and have reduced

self-esteem and self-efficacy because of their older age (Chrisler, Barney, and Palatino, 2016; Choi, Kim, Chipalo, et al.,

2020). Due to the negative effects of internalized ageist stereotypes, older women may have lower self-confidence and

believe that they are not capable of using the Internet when they become older, especially when they have functional

32 International Journal of Population Studies | 2020, Volume 6, Issue 2