Page 57 - MI-2-4

P. 57

Microbes & Immunity Management of obesity

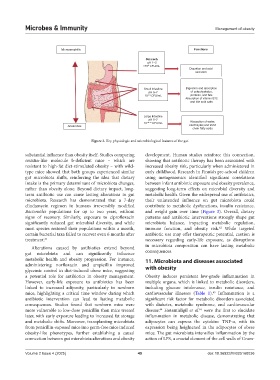

Microaerophillic Functions

Stomach

pH 1–2

<10 CFU/mL

2

Digestion and acid

secretion

Small Intestine Digestion and absorption

pH 6–7 of carbohydrates,

10 1–9 CFU/mL proteins, and fats

Absorption of vitamin B12

and bile acid salts

Large Intestine

pH 5–7

10 10–12 CFU/mL Absorption of water,

Anaerobes electrolytes,and short

chain fatty acids

Figure 2. Key physiologic and microbiological features of the gut

substantial influence than obesity itself. Studies comparing development. Human studies reinforce this connection,

resistin-like molecule b-deficient mice – which are showing that antibiotic therapy has been associated with

resistant to high-fat diet-stimulated obesity – with wild- increased obesity risk, particularly when administered in

type mice showed that both groups experienced similar early childhood. Research in Finnish pre-school children

gut microbiota shifts, reinforcing the idea that dietary using metagenomics identified significant correlations

intake is the primary determinant of microbiota changes, between infant antibiotic exposure and obesity prevalence,

rather than obesity alone. Beyond dietary impact, long- suggesting long-term effects on microbial diversity and

term antibiotic use can cause lasting alterations in gut metabolic health. Given the widespread use of antibiotics,

microbiota. Research has demonstrated that a 7-day their unintended influence on gut microbiota could

clindamycin regimen in humans irreversibly modified contribute to metabolic dysfunctions, insulin resistance,

Bacteroides populations for up to two years, without and weight gain over time (Figure 3). Overall, dietary

signs of recovery. Similarly, exposure to ciprofloxacin patterns and antibiotic interventions strongly shape gut

significantly reduced gut microbial diversity, and while microbiota balance, impacting metabolic regulation,

most species restored their populations within a month, immune function, and obesity risk. While targeted

62

certain bacterial taxa failed to recover even 6 months after antibiotic use may offer therapeutic potential, caution is

treatment. 61 necessary regarding early-life exposure, as disruptions

Alterations caused by antibiotics extend beyond in microbiota composition can have lasting metabolic

gut microbiota and can significantly influence consequences.

metabolic health and obesity progression. For instance, 11. Microbiota and diseases associated

administering norfloxacin and ampicillin improved with obesity

glycemic control in diet-induced obese mice, suggesting

a potential role for antibiotics in obesity management. Obesity induces persistent low-grade inflammation in

However, early-life exposure to antibiotics has been multiple organs, which is linked to metabolic disorders,

linked to increased adiposity, particularly in newborn including glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, and

mice, highlighting a critical time window during which cardiovascular illnesses (Table 1). Inflammation is a

63

antibiotic intervention can lead to lasting metabolic significant risk factor for metabolic disorders associated

consequences. Studies found that newborn mice were with diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular

64

65

more vulnerable to low-dose penicillin than mice treated disease. Hotamisligil et al. were the first to elucidate

later, with early exposure leading to increased fat storage inflammation in metabolic disease, demonstrating that

and metabolic shifts. Moreover, transplanting microbiota adipocytes can express the cytokine TNF-α, with its

from penicillin-exposed mice into germ-free mice induced expression being heightened in the adipocytes of obese

obesity-like phenotypes, further establishing a causal mice. The gut microbiota intensifies inflammation by the

connection between gut microbiota alterations and obesity action of LPS, a crucial element of the cell walls of Gram-

Volume 2 Issue 4 (2025) 49 doi: 10.36922/MI025160036