Page 38 - IJPS-7-1

P. 38

Breakpoint model application to Turkish population growth

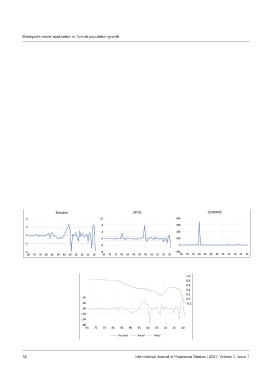

(Figure 3) are showing that observations of 1979 – 1981, 2000 – 2001, and from 2017 until 2021 are outliers. According

to COVRATIO’s plot (Figure 3), it can be seen that only the observations of 1979 – 1981 have very huge outliers.

Casual check of the residuals suggests that our model is a very good one and that there is no need to be improved with

the additional breakpoints. The corresponding actual, fitted, and residual plot is given in Figure 4:

4. Discussion

Population policies of Türkiye may be analyzed in two periods; the pronatalist period from 1923 – 1960 and antinatalist

periods from 1960 to 2000 (Yüksel, 2015; Yüceşahin, Adalı, and Türkyılmaz, 2016). In the middle of 1950s, population

policy has been questioned as a result of the fast and not planned urbanization, illegal and harmful to health abortions, as

well as lack of public investment for the new cohorts. After the 1960 military takeover, the newly established State Planning

Organization and the Turkish Ministry of Health were involved in creating antinatalist policies. Current planning in Türkiye

has its origin in the 1961 Constitution, since when planning for social and economic development has been defined as the

responsibility of the state (Baran, 1971). The State Planning Organization (SPO) is a government organization having an

obligation for drawing up the 5-year plans as well as the annual programs. Since its establishment, the 5-year plans have

been drawn up in Türkiye. Furthermore, the duty of the SPO has also to follow up the implementation of the plans and to

counsel the government on ongoing economic policy issues (Baran, 1971). The first development plan including antinatalist

policies was legalized by the Turkish Parliament in 1965 and the “557 numbered Population Planning Law” was enacted

(Yüksel, 2015). Thus, the beginning of the 1960s is accepted as the breaking point for policy change. The 1960s indicate

the beginning of the “planned era” in Türkiye, where 5-year development plans have been preparing to assess the current

social, economic, and demographic situations and put related goals (Yüceşahin, Adalı, and Türkyılmaz, 2016). Afterward,

almost all consequently 5-year development plans between 1965 and 2007 (total eight) are engaged with the population

and development relationship and have been indicating the need for controlling the POPG (Yüksel, 2015). As Yüceşahin,

Adalı, and Türkyılmaz (2016) emphasize, as from 2008 onward, a new-third pronatalist policy period came into the Turkish

scene. A first sign of a new pronatalist policy was given in 2008 by the then-prime minister and current president Recep

Tayyip Erdoğan proposing that families should have at least three children (Yüceşahin, Adalı, and Türkyılmaz, 2016).

Further signs of the new pro-natalist policy include debates on restrictions on induced abortion and cesarean sections, as

well as initiatives for longer maternity leave, early retirement schemes for mothers, and one-time child benefit payments.

Figure 3. Influence statistics: Breakpoint model for population growth in Türkiye, 1965 – 2021. Source: Author’s design based on real data.

Figure 4. Residual plots: Breakpoint model for population growth in Türkiye, 1965 – 2021. Source: Author’s design based on real data.

32 International Journal of Population Studies | 2021, Volume 7, Issue 1