Page 73 - IJB-10-2

P. 73

International Journal of Bioprinting Advancements in 3D printing

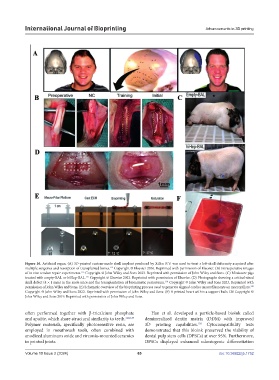

Figure 16. Artificial organ. (A) 3D-printed custom-made skull implant produced by Xilloc B.V. was used to treat a left-skull deformity acquired after

115

multiple surgeries and resorption of transplanted bones. Copyright © Elsevier 2016. Reprinted with permission of Elsevier. (B) Intraoperative images

116

of in vivo tendon repair experiments. Copyright © John Wiley and Sons 2023. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley and Sons. (C) Miniature pigs

117

treated with empty-BAL or hiHep-BAL. Copyright © Elsevier 2023. Reprinted with permission of Elsevier. (D) Photographs showing a critical-sized

118

skull defect (4 × 1 mm) in the nude mice and the transplantation of biomimetic periosteum. Copyright © John Wiley and Sons 2023. Reprinted with

119

permission of John Wiley and Sons. (E) Schematic overview of the bioprinting process used to generate aligned cardiac macrofilaments on macropillars.

Copyright © John Wiley and Sons 2022. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley and Sons. (F) A printed heart within a support bath.120 Copyright ©

John Wiley and Sons 2019. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley and Sons.

often performed together with β-tricalcium phosphate Han et al. developed a particle-based bioink called

and apatite, which share structural similarity to teeth. 128,129 demineralized dentin matrix (DDM) with improved

Polymer materials, specifically photosensitive resin, are 3D printing capabilities. Cytocompatibility tests

130

employed in mouthwash tools, often combined with demonstrated that this bioink preserved the viability of

anodized aluminum oxide and zirconia-mounted ceramics dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) at over 95%. Furthermore,

in printed joints. DPSCs displayed enhanced odontogenic differentiation

Volume 10 Issue 2 (2024) 65 doi: 10.36922/ijb.1752